by TRISH RUDDER

Born in Green Bay, Virginia on August 17, 1922, Luther Robertson became a Morgan County resident in the 1970s.

He just turned 98 on Monday.

His story so far includes meeting and shaking the hand of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in Washington, D.C. when he was first employed at D.C.’s Union Station.

This happened in 1941 before the country entered World War II.

His story also includes the time a runaway train crashed into Union Station in 1953.

Retracing his steps

Robertson grew up on a 300-plus acre farm in Virginia.

He was graduated from high school in 1941 in Victoria, Va. where he had a high school sweetheart, Betty. They were married during the war, had three children and were together for 61 years before Betty passed in 2003.

After a brief job with the railroad in Virginia after high school, he went to Washington D.C. to room with one of his brothers and look for work.

Robertson got a job at the passenger rail station in D.C. — Union Station – which would be one of the first of a long career there working his way up the ladder at Union Station as a train schedule recorder, a ticket examiner, duty manager, assistant stationmaster and then stationmaster before retiring at age 60. He worked there for 41 years.

At that early job, he put incoming and outgoing train schedules on a six-foot by 20- foot board.

“The first two days I worked as a helper then I worked by myself,” Robertson said.

One time he learned that a train was four hours late and was approached by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt who wanted to know why it was late.

Mrs. Roosevelt was not too happy with Robertson. “What’s going on?” she said.

Robertson said he took Mrs. Roosevelt and one of her aides and a secret service member to sit in the stationmaster’s office, while other secret service members were outside the office.

“How can you make up an hour,”? Mrs. Roosevelt had asked when four hours became three.

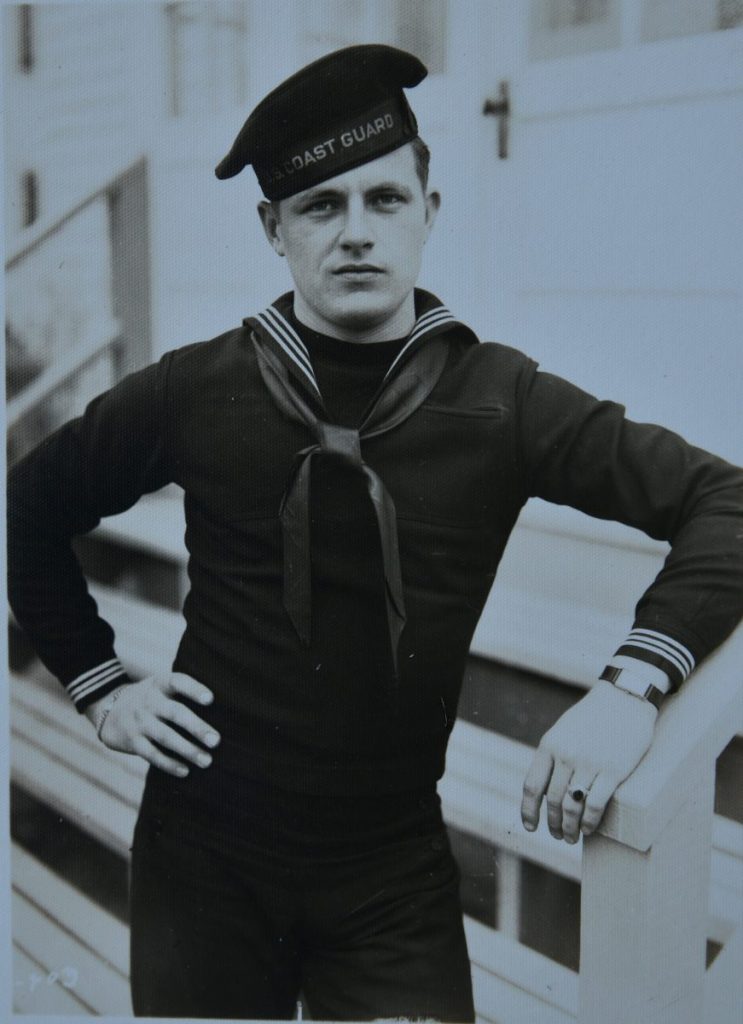

Luther Robertson in his U.S. Coast Guard uniform in 1942 in Curtis Bay, Md. during World War II. He served as a military police officer.

“I found out why,” Robertson said.

“The Ohio train hit a logging truck. It was damaged but could still run but only at 35 mph to 40 mph later. It finally met another train and was able to switch engines and made up some time by traveling at 90 mph,” he said. He told Mrs. Roosevelt that, but she was annoyed with the fact that her schedule was ruined.

The War Years

When the United States entered World War II, Robertson joined the United States Coast Guard in January 1942 to avoid being drafted as his two brothers were.

He was sent to the Coast Guard Yard in Curtis Bay, Md. outside Baltimore for boot training.

“There were rumors that we were going to be sent to Alameda, Ca. to go to board a submarine. Then the next rumor was that we were going to go on the sub.”

Robertson said he was claustrophobic, and he would not do well on a submarine.

“I prayed that if that was so, that the commander would shoot me.”

“The commander called us to form a line. He then chose 28 of us to ‘step out,’ and we were to go and follow instructions to get on a Greyhound bus.”

Robertson was relieved.

“We were not going to go on a submarine. Instead we were bussed to Goucher College, a girl’s college in North Baltimore. We were housed on the fourth floor. The girls were on the first three floors, but we never saw them often. Only when it was hot and when we got back to the barracks at around 3 a.m., we saw the girls sleeping outside on the grass.”

Robertson was also trained to become a military police officer at the Coast Guard Yard.

As a military police officer, Robertson worked on East Baltimore Street. He was in charge of his men, and he and his team had to round up problem military men in bars who drank too much and were causing trouble.

“I drove the paddy wagon,” he said.

He said at times there were from 3,000 to 6,000 men on ships and many were granted leave to roam the East Baltimore Street establishments.

When he had to pick them up, they were taken to the police station and the next day they were taken back to the ship.

Robertson carried a police stick. One time he was in a bar and the bartender needed help with one of the problem men.

“Mate, the bartender said you had enough,” Robertson had said.

“And the drunken man took a swing and he hit me on the left shoulder. I knocked off part of his ear with my billy club. We took him to the hospital, and they glued it back,” Robertson said.

“He was a big-league boxer from Detroit. It took three of us to handcuff him.”

Robertson also carried a gun, but he never had to use it.

Money was tight

Robertson wanted to move his wife, Betty and their son to Curtis Bay, but he had a hard time finding a place they could afford to rent and buy groceries, too.

Two of his mates’ wives shared a place but neither could cook. They offered Robertson a deal that if Betty would do the cooking, they would buy the food and she could stay there with their wives. The wives each had a bedroom, so Betty and their son slept on a blow-up mattress on the floor in the kitchen.

He said Betty was a good cook already, but she studied cookbooks to perfect her skills and expand her collection.

They were out walking one day and their son, Linwood, was playing ahead of them on the sidewalk. A woman came up to them and was admiring their son and even spoke of her wish to have a baby herself. They ended up going into her house, and Betty told the woman they were looking for a place to stay.

The woman offered them a deal: they could stay in her house if they paid the taxes and utilities while she was in California.

“We lived in the house about three years,” Robertson said.

There was a public telephone with an enclosed booth that everybody on the street used for their personal calls, since having your own phone was too expensive. The woman kept in touch through phone calls to the Robertsons, he said.

Returning to Union Station

After the war, Robertson returned to the Washington D.C. area and got his old job back at Union Station recording incoming and outgoing trains. He then was promoted after two years to ticket examiner, and then to duty manager, and then to assistant stationmaster at 27 years old.

A runaway train coming from Boston, Mass. on January 15, 1953, five days before Dwight D. Eisenhower was sworn in as President of the United States, crashed into Union Station.

The train destroyed the stationmaster’s office at the end of the track, took out a newsstand and was on its way to crashing through the wall of the lobby, but the engine and two cars fell through the main floor of the terminal into the basement, which is now the food court.

Robertson was the stationmaster at that time. He said the station was alerted that a runaway train was on its way and everyone in the station ran out of the building.

About 40 people were hurt but none died, he said.

“It was traveling at 60 mph and if it hadn’t hit the cement abutment, it would have gone to the Capitol,” he said.

The 1976 movie “Silver Streak” that starred Gene Wilder, Jill Clayburgh and Richard Pryor used that train wreck as the finale in the movie.

His wife, Betty, was pregnant with their third child and went into labor that same day after Robertson left for work. She saw the news report on television. “The accident reported no deaths ‘at the moment,’” Robertson said. “And there was no way to call her to tell her I was okay,” he said.

Robertson was at the station for two days before he got home to meet his new daughter, named Betty.

He said a temporary floor was built in the station in three days before Eisenhower’s inauguration.

“We worked ‘round the clock to get the train station as close to normal as possible to accommodate all the travelers coming in for the inauguration,” he said.

Before Eisenhower became president, President Harry Truman, his wife Bess and his daughter Margaret traveled by train, and Robertson would be alerted of their arrival.

The Secret Service would come one hour earlier before the president came to the station, Robertson said.

When Margaret took the train to New York on Friday evenings to spend the weekend, President and Mrs. Truman would see her off.

“One time he [Truman] was standing next to me on the platform, and I said we had a new electric engine and asked if he’d like to see it. He said he would, and I motioned for him to climb the ladder to go into the engine.”

“He started up the ladder, and a secret service man pulled the president back and said, ‘I’ll go first.’ And up the stairs he went.”

“President Truman put his hand on my shoulder and said: ‘It doesn’t matter if you’re at the top, someone is going to be always ordering you around.’”

When President Truman and his family left to go to St. Louis, Missouri after Eisenhower was inaugurated, they boarded the rear car so they could wave goodbye to those citizens standing along the way.

“The business car is a much nicer car,” Robertson said.

Robertson said President John Kennedy only took the train to go to Army-Navy football games.

As stationmaster, Robertson received a letter from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover stating he found dust on the windowsill of his sleeper car on his trip to Florida. He wrote in the letter that the train was filthy.

That happened only one time, Robertson said, because as soon as a train arrived from New York where it began, and Mr. Hoover was scheduled to board it in D.C., he had a cleaning person inspect the sleeper car and wipe down Hoover’s windowsill to make sure no dust had accumulated from New York to Washington. He said dust does get inside the cars, but Mr. Hoover thought the cars were not being cleaned properly.

Robertson also remembered the time a popular singer was a passenger in a sleeper car that was trimming his toenails with a razor blade and cut his toe. He wanted the train to wait while he visited the emergency room.

Robertson said the singer was told the train could not be held for him.

The cut toe was bandaged and had stopped bleeding on its own, Robertson said.

Robertson developed contacts and working relationships over the years and when accidents happened, he knew who to call to get problems solved, he said.

Robertson said when there were any train wrecks, he would find school buses in Harrisburg, Pa. and in the Washington-Baltimore area close to the scene to get the people off and onto another train.

Moving to Morgan County

He and his family lived in Takoma Park, Md. until Robertson and his wife, Betty moved to Berkeley Springs in the 1970s and had a house built on Silver Road.

Betty Robertson’s sister-in-law bought property on Silver Road in Berkeley Springs and they all camped on it, Robertson said. He and Betty bought the property next door that had an old house on it. They used the old house at first until they had a new house built.

In 1970, they sold their Takoma Park home. After the Berkeley Springs house was built, as stationmaster, Robertson worked three 12-hour days and then would go home to Berkeley Springs for two days. He had an apartment in Takoma Park because he was “on call” and had to get back to work quickly.

“It was not a five-day work week,” he said, and he worked weekends. He had three assistants, he said.

When the passenger rail service was taken over by Amtrak in 1971, Robertson’s title was changed from stationmaster to general manager.

He retired at age 60.

In 2001, the Robertson’s moved to the current house off Fairview Drive where he lives now.

Betty Robertson died in 2003. Robertson married a widow, Helen, two years later. Their marriage lasted 10 years until she died in 2015, he said.

On Sunday, August 9, Robertson’s daughter, Betty Leach, and her family surprised him at his home with an early birthday celebration.