Two brothers made their way from Bath to freedom via the Underground Railroad

by Kate Shunney

An unlikely journey by two brothers from enslavement to freedom began here in Morgan County during early February of 1837.

The two men — named by their enslavers as “Patrick” and “Abraham” – are said to have escaped from the Fruit Hill Farm of Col. John Sherrard where they were considered his personal property.

The lengthy and violent path to freedom of Abraham, aged 20, and Patrick, aged 21, is one of the stories commemorated by the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, a project of the National Park Service.

Historical marker, part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Dr. Barb Zaborowski is a Pennsylvania historian and researched the story of Patrick and Abraham’s escape after focusing on the Underground Railroad in a county-wide reading program she ran for middle school students in 2008.

That research into Underground Railroad activity in the Johnstown area led Zaborowski to the story of the two brothers.

“That’s when I discovered the story of Patrick and Abraham and I’ve been chasing the story ever since…my ultimate goal will be to find out where they ended up…I still don’t have an end to the story,” she said.

Zaborowski’s research got a Johnstown site added to the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom project.

Most of the efforts to shepherd the two men away from slave hunters took place in Pennsylvania, but their escape began here.

Zaborowski got in touch with Town of Bath Recorder and former mayor Susan Webster to gather more information about the start of the brothers’ journey. Webster showed Zaborowski portions of the Fruit Hill Farm property, including a tombstone for John Sherrard that’s still on the property.

“I knew our property had great historic significance,” Webster said in an email about Zaborowski’s research, “but had never heard anything about a connection to the Underground Railroad history.”

John Sherrard owned hundreds of acres of land around Morgan County (then Virginia) but his Fruit Hill Farm was located along the top of Warm Springs Ridge above the area where the Berkeley Castle now stands, and down along the west-facing side of the ridge heading toward Sir John’s Run, Cold Run Valley and angling down to the run.

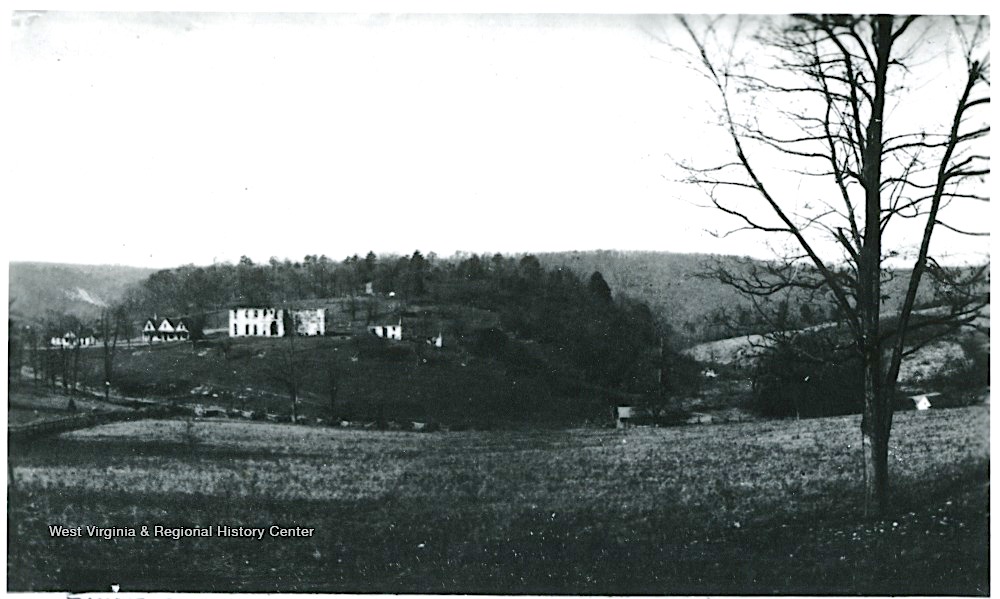

Undated photo labelled “Fruit Hill Farm” from the West Virginia & Regional History Center.

A February escape

According to multiple sources, Patrick and Abraham left the Sherrard farm in what is now Berkeley Springs either on February 10 or February 12, 1837. Their departure was the start of a dangerous race to outrun and elude men paid to capture them and return them to the farm and ownership of Sherrard.

That journey took the brothers west from Fruit Hill Farm, across the Potomac River and north along what appears on maps to be Sideling Hill Mountain. They reportedly spent their first night in Everett, Pa. – more than 35 miles from Bath.

From there, the men made it to St. Clairsville, then the Johnstown area, which was a “recognized station” on the Underground Railroad, according to Zaborowski’s research.

She relied on accounts from county histories in Cambria and Bedford, and other sources that captured the story of the brothers.

In spite of help from dedicated abolitionists in the area, Patrick and Abraham were pursued by slave hunters. History accounts say the Sheriff of Bedford County found the brothers in a “chopper’s cabin” on the side of a mountain where they hid overnight. Accounts say the lawman knocked one of the brothers down with an axe handle and was about to pin him down when the other brother attacked, cutting the officer severely with a pocket knife and leaving the area.

Sheriff’s deputies arrived shortly after, and the brothers were then pursued by eight or 10 men for another 20 miles. After hiding for the night, Patrick and Abraham were found again. During a fight to escape, the brothers encountered hunters who shot them in the shoulder and knee, having been told by deputies that the black men were murderers, history accounts say.

Wounded & captured

Wounded, the brothers were captured and taken to the farm house of William Slick, who happened to be an agent of the Underground Railroad.

While the men were put under arrest by the Constable of the area for being runaway slaves, agents of the Underground Railroad conspired to get the brothers medical treatment for their gunshots.

Once the men were recovered enough from their injuries, they were called to the Court of Common Pleas to answer the charge of being fugitives. In a last-minute operation, members of the Underground Railroad schemed to make it appear that the men’s wounds had reopened and were gushing blood, making the keeper of the slaves run off in search of a doctor. By the time the guard and doctor returned, the runaways were gone.

Court records from February 27 of 1837 show that the Constable reported the brothers had escaped on February 24th, and he accused several local men of “aiding and assisting the said Black men away from his custody.”

“The truth was, that as soon as the wounded boys were able to travel, their friends had filled the bed of a wagon with hay, on which they were laid and covered with the same light material, and the driver started north through Hinekston’s run road. Under these terrible conditions was the freedom for the fugitives acquired,” reads the History of Cumbria County.

“The master of the slaves offered three hundred dollars reward for their capture, and a few hard-hearted wretches made further effort to reclaim them, when it became necessary to remove them to greater safety, and they were transferred to the Quaker settlement in St. Clair township…and from there they were conveyed to Center county, thence to Clearfied county, and finally on toward Canada, where they probably arrived without further molestation, and remained free from the accursed state of human bondage,” wrote authors in the History of Bedford County.

The “master of the slaves” who offered that reward was one of the early civic leaders of Morgan County, well-known to many as the county formed in 1820.

Land records in the Morgan County Clerk’s office aren’t clear how large a farm John Sherrard owned or worked, as individual parcels passed back and forth to him several times during the early days of the county.

One land record refers to a parcel of 300 acres as “All that certain tract of land known as Fruit Hill Farm.”

An 1834 record says three tracts totaling 159 acres were bought by Sherrard near the Town of Bath for $325 from the Orricks and Wolfes.

There are references to the “Fruit Hill” tract well into the last years of the 19th century, decades after Sherrard’s death in April 1837 — the same year the brothers escaped his enslavement.

Little to nothing is recorded in land records about enslaved people or hired helpers on Sherrard’s farm, or what crops he grew or traded.

Col. John Sherrard was himself well-known.

He attended the first meetings of the Morgan County Court in April of 1820. He was one of several men who made up the court to conduct the new county’s business. The Sherrard’s were a powerful family in those first days of the county.

Historian Fred Newbraugh wrote, in Morgan County, West Virginia and Her People, “The power of government was taken over by Molly Abernathy, her husband William and two lawyer sons, John and Joseph Sherrard, by a previous marriage.”

Newbraugh goes on to describe the tight hold the Sherrard family had on county government, from serving as Justices of the Peace, deputy sheriff, delegate to the Virginia Assembly, treasurer of the school fund and Major in the County Militia.

After John Sherrard died in 1837, his brother and mother moved to Winchester, letting the county move into an era released from their hold.